Light-Weight RefineNet

After nearly two years from my first publication (at the same venue as now), which included a year of academic break, I have finally submitted my first paper in my new PhD journey to the BMVC conference, which will take place from Sep, 3 to Sep, 6 in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. This time it took me a month more for the submission, although all the main results were in place already in March.

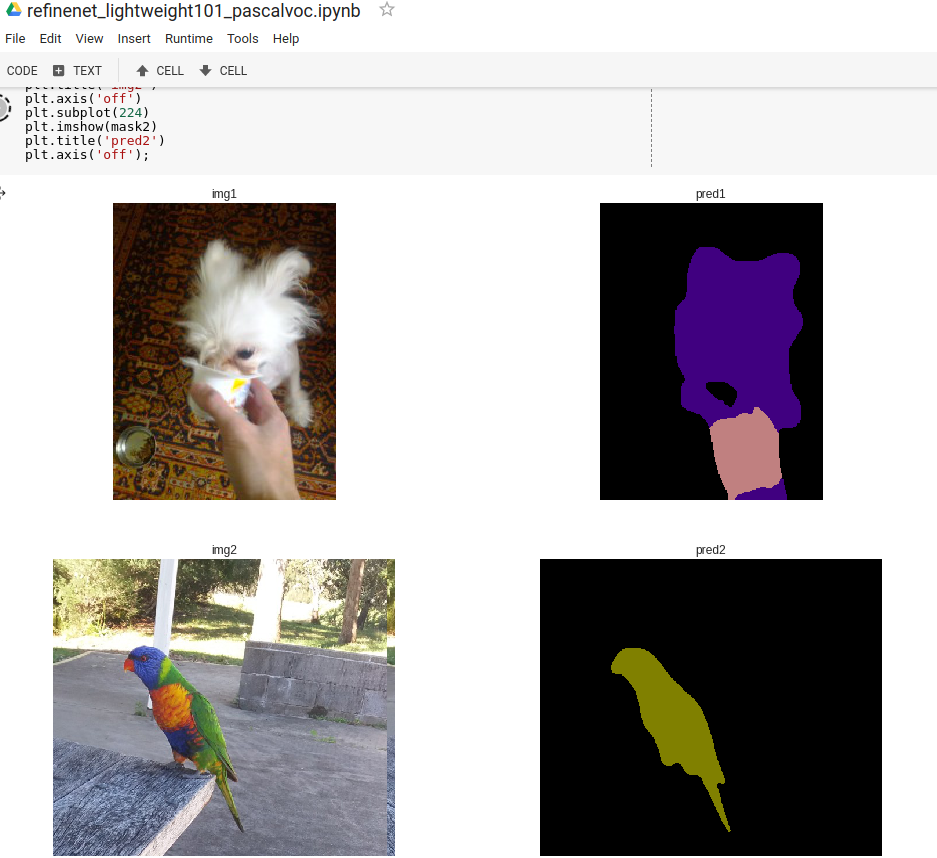

Below are some cheesy qualitative results of one of our models recognising and segmenting my lovely dog, Emmy.

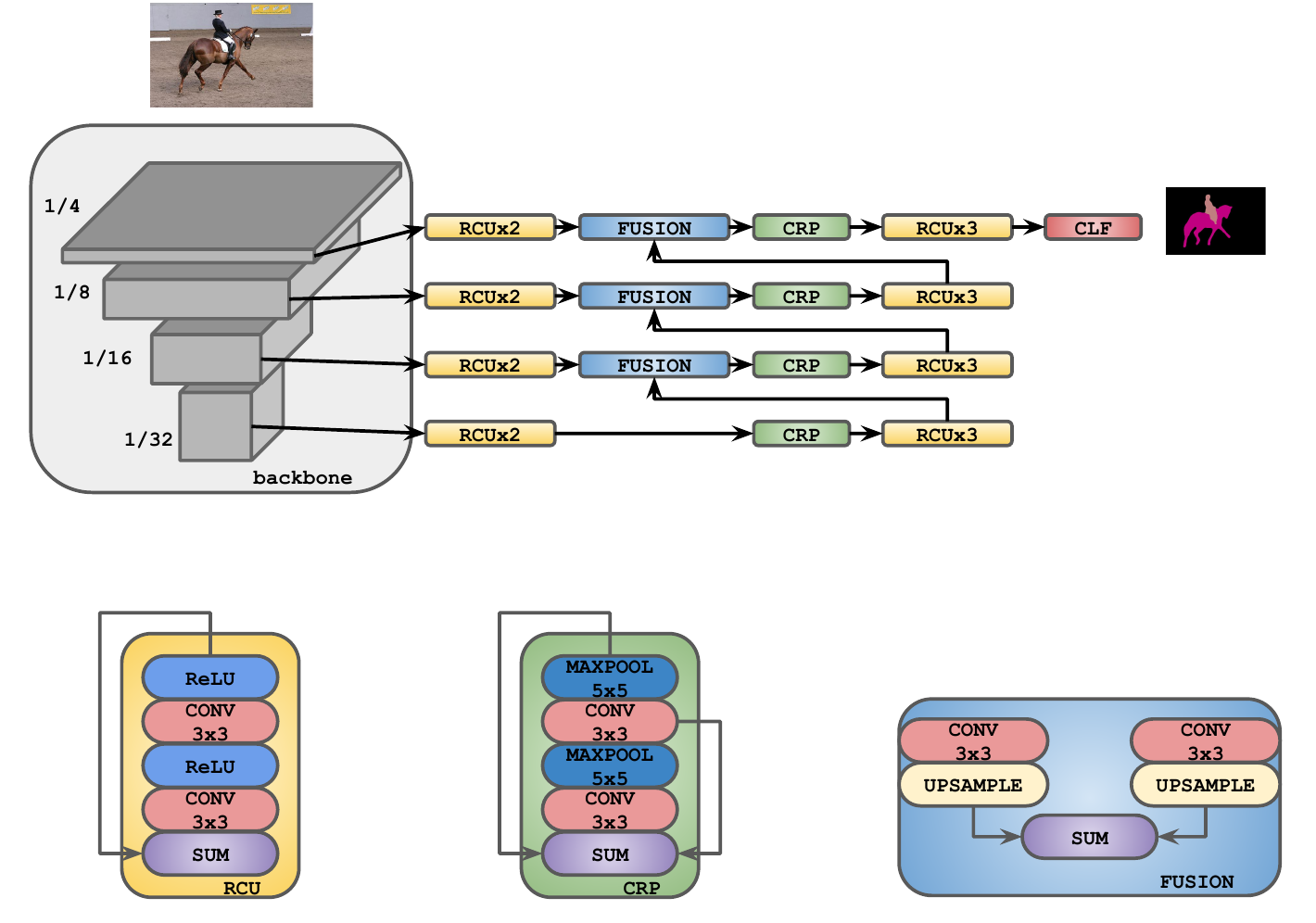

Anyway, let us move on to the topic of the paper itself. From the title, it is becoming apparent that the paper is dealing with an adaptation of original RefineNet into the one suitable for real-time inference. Of course, it is clear for those of you who have been following semantic segmentation for awhile and have heard of the first RefineNet. For others, I will need to clarify that RefineNet was originally proposed by Lin et al. in 2017 (published in CVPR) for the scene parsing (aka semantic segmentation) task and was achieving state-of-the-art results at that time, outperforming Google’s DeepLab-v2 by a significant margin. It is an encoder-decoder type of network, where decoder can be any of residual networks (such as ResNet-50/101/152). In the decoder part, it relies on two abstractions, called Residual Convolutional Unit (RCU), and Chained Residual Pooling (CRP), respectively. The first one is a simplification of the original residual block with 3x3 convolution followed by ReLU and without batch normalisation layers in-between, while the second is a residual cascaded block with 3x3 convolution followed by 5x5 max-pooling (with appropriate padding). The last output of the classifier (with the resolution of 1/32 from the original input size) is gradually refined (hence, the name of the network) via those abstractions, and recursively summed up with higher-resolution layers from the classifier. Below you can see a visual structure of the RefineNet architecture.

Having said that, I should also answer the question of what is wrong with original RefineNet? Nothing is wrong, believe me, it works well, but there is a room for improvement in terms of runtime (and probably accuracy, as well). And that is what I will be covering below.

But before doing that, I will just highlight how this whole project on speeding up RefineNet came about. In the beginning of November, our Adelaide node was due to hold a demonstration session for few visitors, and my supervisor (and also the leader of the group), Prof. Reid, queried me on whether I would be able to showcase real-time segmentation using RefineNet. By that time, I was close to re-implementing RefineNet in TensorFlow and PyTorch (as the original code was written in MatConvNet), and I was very curious myself whether I would be able to do inference with it in real-time. After purchasing a plain webcamera, I made some benchmarks and found out that it was working (almost) real-time, but only on images of very low resolution. The biggest bottleneck for me was the transfer of data between GPU and CPU. I came up with a ‘hacky’ way of doing sparse predictions in PyTorch, which gave a significant boost on images of size 512x512, but it was not enough to showcase a working demo.

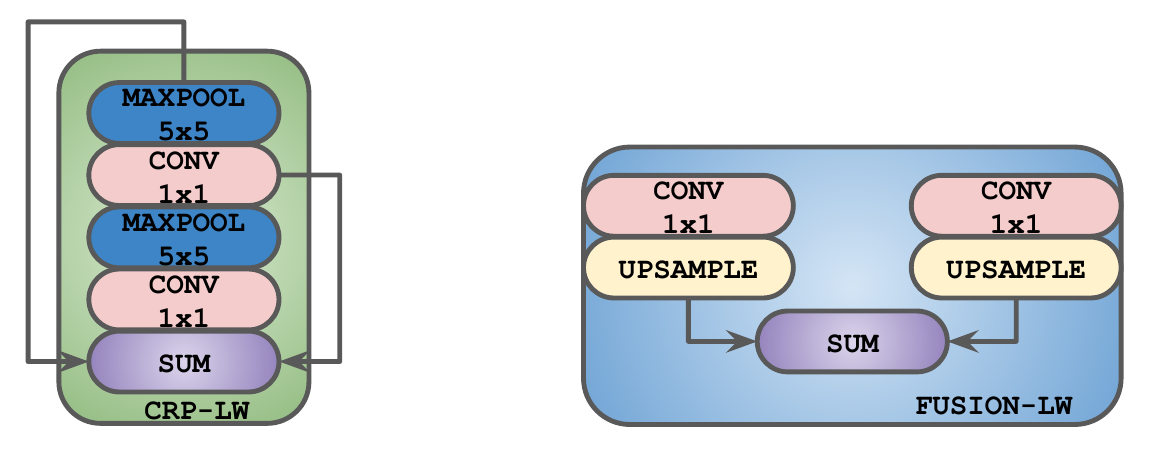

In any case, it did not affect my enthusiasm much and I started a new set of experiments with a light-weight RefineNet architecture, where I replaced all 3x3 convolutions (except for the last classifier) in the RefineNet blocks with their 1x1 counterparts with the goal of saving parameters and increasing runtime. At that time (as I only found out later), my batch normalisation code was completely wrong, but I still managed to get decent results losing around 2-3% to original RefineNet, although significantly speeding up inference time. This was all done in November and I moved on to another projects involving semantic segmentation, and the whole light-weight RefineNet idea was forgotten until January.

In January, I started thinking again about what are the most important parts of the RefineNet architecture, and how we could make the network operate faster without losing any accuracy, and without reverting to methods such as compression, or knowledge distillation (as for those methods you would need to have a large pre-trained model, which is time-consuming). The first observation I made was that there were barely any changes in segmentation scores if we considered only last two levels of ResNet (instead of 4). This gave me quite a marginal boost in runtime, but I was not satisfied with it. Hence I recalled my pre-trained light-weight network and tried to tweak the number of RCU and CRP blocks. First, I removed only one RCU block, and… somehow the result did not change at all. This looked weird, and at the same time quite promising. I continued removing RCU blocks until none were left, and to my biggest surprise, the performance stayed intact. Only later, I inspected the RCU weights and found out that they all saturated. In any case, I also dropped RCU blocks in the original RefineNet, but lost more than 5% mIoU after that, which was when I realised that light-weight RefineNet might be a promising direction to explore. By the way, dropping CRP blocks led to a significant drop in performance, so the importance of that block was clear to me even back then.

Technically speaking, these are the only recipes for light-weight RefineNet: 1) replace 3x3 convolutions with 1x1 counterparts, and 2) drop RCU blocks. Seriously, do that and you will get almost the same performance, more than 2x speedup and more than 3x reduction in parameters.

The above is all good, but what is interesting for me (and I hope for many fellow researchers as well) is why does it work? Why replacing 3x3 convolutions with 1x1 does not hurt performance? Shouldn’t it reduce the global coverage and the receptive field significantly? Why a shallower network produces results on par with the deeper one? These questions are partially covered in the paper, and I will briefly re-iterate them here in a more hand-wavy way. I believe there are more solid theoretical claims that should be made, and I will devote my further research to discover them.

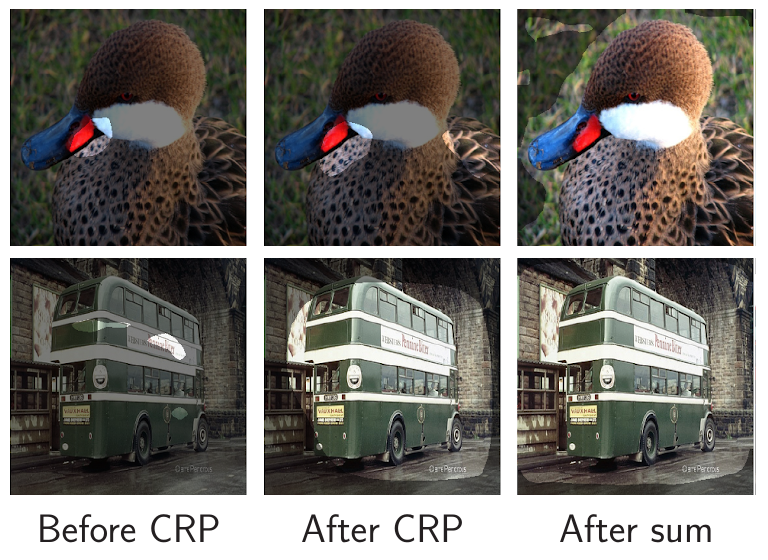

First of all, what we found out is that the receptive field size significantly increases after the summation operation between feature maps coming from layers of different resolutions. It does also increase after the CRP block, but to a less extent. RCU block in this case does not play any important role. In hindsight, it does make sense: deeper layers tend to accumulate more information about large objects in expense of losing details of the small ones, and when summed up with shallower layers, they cover the image more uniformly.

Okay, what we thought next was that the RCU blocks may still be useful for learning new and better features. We conducted a simple experiment to evaluate this claim: in particular, we measured classification and segmentation accuracy achieved with features before RCU, after RCU, and after CRP. The results showed that there was barely any gain in using RCU, and there was a large improvement in accuracy after the features underwent the CRP block. To some extent, this solidified our intuition about why Light-Weight RefineNet was possible, although, as I said earlier, such intuition is still awaiting to be confirmed by a deeper analysis.

More Information

For those interested in this research, please refer to our paper - PDF / SUPP

You can also try out one of our models live in Google Colab - RefineNet-LW-101

References

Original RefineNet - RefineNet: Multi-Path Refinement Networks for High-Resolution Semantic Segmentation

Empirical Receptive Field Size - Object Detectors Emerge in Deep Scene CNNs

Comments