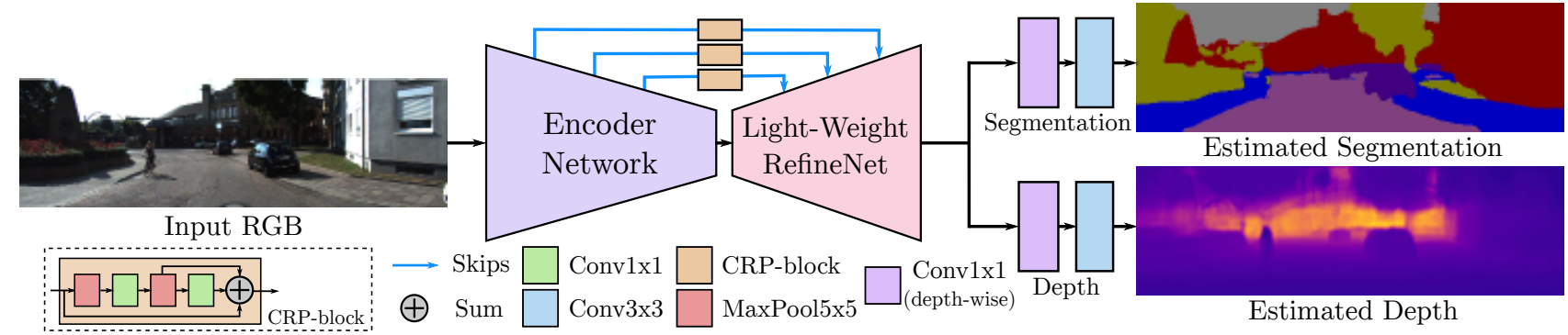

Real-Time Joint Segmentation, Depth and Surface Normals Estimation

Our paper, titled “Real-Time Joint Semantic Segmentation and Depth Estimation Using Asymmetric Annotations” has recently been accepted at International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA 2019), which will take place in Montreal, Canada in May. This was a joint work between the University of Adelaide and Monash University, and it was a great experience for me learning from my collaborators about two dense per-pixel tasks that I had only been vaguely familiar with before: depth estimation – i.e., predicting how far each pixel is from the observer, and surface normals estimation – i.e., predicting a perpendicular vector (normal vector) to each pixel’s surface. Both tasks are extremely valuable in the robotic community, and hence we were motivated to explore the limits of performing three tasks (2 above + semantic segmentation) in real-time using a single network.

|

|---|

| Our network architecture. Each task has only 2 specific layers, while everything else is shared |

In this post I will not go far into technicalities, and instead would want to emphasise our motivations and challenges step-by-step below.

Motivation 1 - “Multi-Task Network”

Small side note: my interests lie on the application side of deep learning and computer vision, thus I tend to think in terms of how practical something is, for example, for edge computing and mobile adaptations. In that sense, taking as an example a hypothetical mobile robot that has to segment the scene and know how far it is from everything around it, one may easily realise that enhancing that robot with two networks for each of these tasks can be a very dubious endeavour.

Firstly, running two networks would be expensive, and, secondly, they would likely to share some computations, thus leading to redundancy in operations. Such redundancy at times can be helpful, but in the world of mobile devices every possible computational saving is a blessing. Hence, what we wanted to have was a single network performing both segmentation and depth estimation at the same time.

Motivation 2 - “Asymmetric Annotations”

A big issue that everyone faces when embarking on a journey towards creating a multi-task network is data. There are very few public datasets that provide annotations for all required modalities. For dense per-pixel tasks, where each pixel must be annotated, the situation is even worse. NYUD has only 1400 images with all annotations for segmentation, depth and surface normals present. KITTI has 200 images annotated for segmentation and depth. These numbers are nowhere near millions for ImageNet or thousands for COCO, and, as widely believed, more data tend to provide better results.

On the other hand, both NYUD and KITTI have a large number of images with depth annotations alone. Certainly, if we were to use them for our joint training, we would achieve at least as good numbers on segmentation as without them and better results on the depth task. Motivated by this, to balance out our training we decided to cheaply acquire missing segmentation labels by running all images with depth annotations only through so-called expert models - those are large models that achieved competitive results on the dataset of the interest (for NYUD, we directly used Light-Weight RefineNet-152) or on a similar set (for KITTI images we used ResNet-38 pre-trained on CityScapes). This is a direct application of knowledge distillation.

Motivation 3 - “Real-Time Multi-Task Network”

Having figured out our training regimes, we embarked towards another of our goals – performing all tasks in real-time. Again, returning back to the mobile robot analogy, we would want robots around us to have low latency – no one would want to wait forever for the robot that was sent off to get us a can of Coke.

Having just adapted a powerful segmentation network for real-time performance, we wondered whether the same trick would be applicable for the multi-task scenario. To this end, naively adding another head for each task did not work well as the number of floating point operations dramatically increased. The cause of that increase was laying in the last convolutional layers where we were operating on features of (¼) resolution from the original size and were performing a standard 1x1 convolution. Changing that standard convolution into its depthwise counterpart, we were able to keep the number of FLOPs under control.

Results

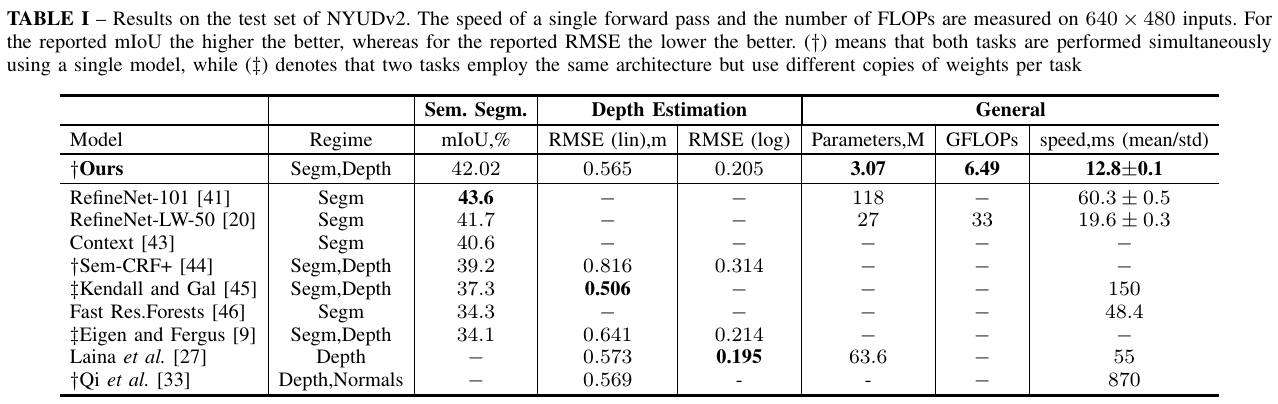

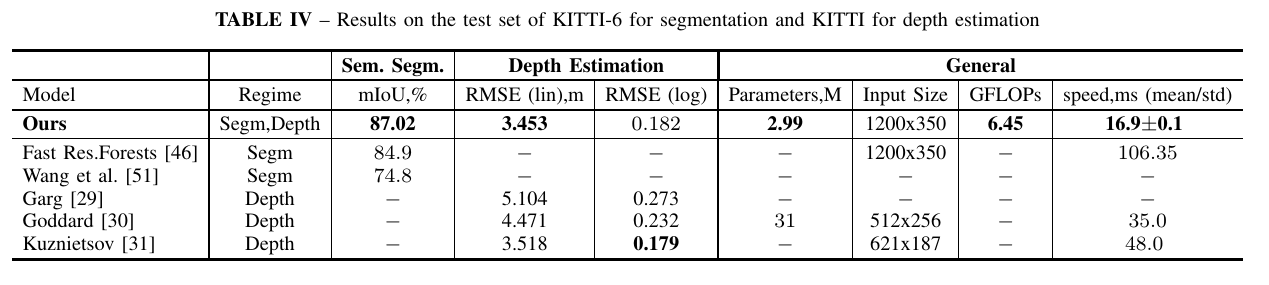

We first tested out our approach for joint segmentation and depth estimation on two popular benchmarks – indoor dataset, NYUDv2, and outdoor KITTI. On both we achieved compelling results, overcoming several heavier networks and performing two tasks in real-time.

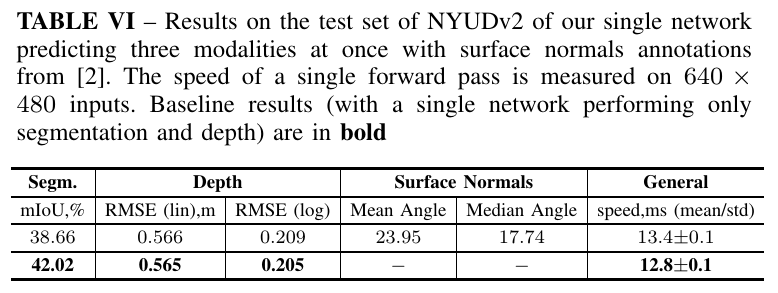

Then we tested out three extensions: in the first, we wanted to see whether we could do more tasks in real-time – as a third task we considered surface normals on NYUDv2. We did not tune our extensions and simply used the same setup as for two tasks although with more data.

As evident from the table above, the segmentation performance dropped significantly, quite possibly due to a large amount of noise in synthetic labels.

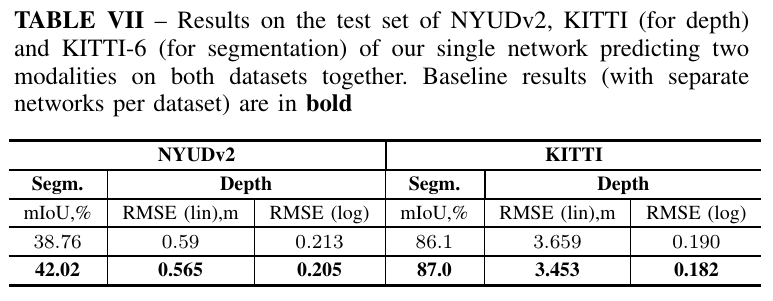

The second extension was done to evaluate whether a single network could solve two tasks on two datasets simultaneously. To this end, we concatenated NYUDv2 and KITTI such that the segmentation head would predict 46 classes (40 from NYUDv2 and 6 from KITTI).

As images from two datasets are quite different, the network did not have any trouble solving both of them simultaneously. I tested out that network on the campus, and from my visual observations, I would say it does work well on unseen data – inside the office, it reliably predicts depth measurements in range of 0-15m while outside in range of 10-40m.

I am currently interested in continuous learning for dense per-pixel tasks, where ideally you would want to have a single network being incrementally improved, and for me witnessing a single network solving two datasets at once is a good sign that there is enough capacity for the incremental setup. I would not want to train a separate model on my robot for each possible dataset, that’s for sure.

Our final extension was about showcasing that depth measurements and segmentation maps produced by our network can be used directly inside a dense semantic SLAM system – namely, SemanticFusion. Obviously, without temporal coherence our point cloud was nowhere near the quality of the one produced by Kinect, nonetheless, the results were still impressive. With more and more end-to-end solutions developed for SLAM, the proposed approach can be directly extended and potentially further improved.

Discussion

There are several interesting points that can be taken from this research, and, on some of them I am actually already working, so any comments or suggestions would be welcome.

Firstly, to what end can we rely on already existing models as experts that provide missing annotations? What we showed is that the synthesis of existing labels with synthetic ones leads to better results, but what we saw with the first extension is that the performance degrades when many noisy labels are used. How to overcome that and how can we filter out unreliable labellings?

Secondly, what we did not cover here is the way of designing where to branch out into certain tasks. I believe AutoML solutions should be a good fit for that; in fact, I already have some preliminary results (that await proper tuning and training).

Thirdly, what is the capacity of a given network? If we were to add more tasks into our architecture, would their performance still be reasonable? If not, when do we stop adding more tasks?

The final point is mostly about the SLAM extension: the depth predictions can vary dramatically with small changes in the input image – the same can be said about semantic segmentation. How do we achieve temporal coherence in these cases? Current solutions in video semantic segmentation tend to rely on optical flow, which significantly slows down the inference speed. On the other hand, would an addition of a single loss function solve the problem, or would we need totally different mechanisms?

Takeaway Points

-

It is possible to perform several dense-per-pixel tasks at once in real-time with a good overall quality. While in research we mostly care about achieving better numbers at each separate task / dataset, future robots must not follow that approach – instead, they will benefit from sharing their computational loads (perhaps, together with other robots)

-

Even with few annotations available one can still achieve solid results. The trick is in transferring knowledge – either directly by fine-tuning (if the model stays the same), or by creating synthetic labels (knowledge distillation)

-

Compact networks can be considered as ideal candidates in the feature extraction pipeline – for example, depth predictions together with segmentation maps can easily be plugged into semantic SLAM systems. If we figure out the right way of making those predictions stable across time, we will get very reliable and very fast solutions for many robotic cases.

More Information

For those interested in this research, please refer to our paper - PDF

All the trained models are available here

Comments