My internship at Skydio

Recently I returned to Australia from the US where I had spent five months as an intern at Skydio, a Redwood City-based startup that is building autonomous flying robots, aka drones. In this post, I will share what I learned during my stay in the US.

In the months preceding my departure, my partner and I spent our evenings watching the Silicon Valley TV series, in some sort of preparation for whatever was awaiting me in the Bay area. As it turned out, Skydio is moving towards their goals in a much less chaotic way than Pied Piper. One of those goals (and also the major selling point of Skydio drones) is the vision-based autonomy engine – primarily, obstacle avoidance and subject tracking. These two key technologies are constantly being improved to mitigate any worries about crashing or losing your drone.

My internship started in the middle of June exactly one week before the CVPR conference. Close to my arrival, I was informed that Skydio had been working on their second release and that the whole pre-launch and launch periods would coincide with my stay there. As my primary goal was to get relevant industry experience, I could not ask for more: working at a start-up that is about to release their second product? Hell yeah!

Back then there were no public videos or images of Skydio’s second drone, Skydio 2. With the first product, R1, Skydio did indeed build a great autonomous vehicle but put a very expensive label of nearly 2500$. The second product is much smaller and cheaper (999$), and instead of 13 cameras has 7. These cameras provide the system with the ability to see in all directions, including above and below the drone body. All but one are so-called navigational cameras, used for perceiving the environment and estimating distances to nearest objects and obstacles in real-time while planning a safe trajectory. The feed from the main camera, or subject camera, is what the end-user sees.

The computational brain of Skydio drones is an NVIDIA Jetson embedded platform – TX1 for R1 and TX2 for Skydio 2. As stated in the specs of the second product, Skydio runs 9 deep networks in flight in real-time. For comparison, Tesla cars (much larger autonomous vehicles with much more power resources available) run 48 neural networks both on their customised neural chip and in the cloud according to the recent talk by Andrej Karpathy.

Returning back to the navigational cameras, I must mention that these are fish-eye rolling shutter cameras. As per the first video below, fish-eye lenses produce ultra-wide-angle spherical images capturing most of the environment’s context. The second video below, on the other hand, demonstrates the rolling shutter effect – the way of scanning the scene not instantly (as in global shutter cameras) but continuously in time. This continuous scanning leads to various distortion effects which may present a significant challenge for any vision algorithm. At the same time, rolling shutter cameras are significantly cheaper, partially explaining the lower price of the second drone.

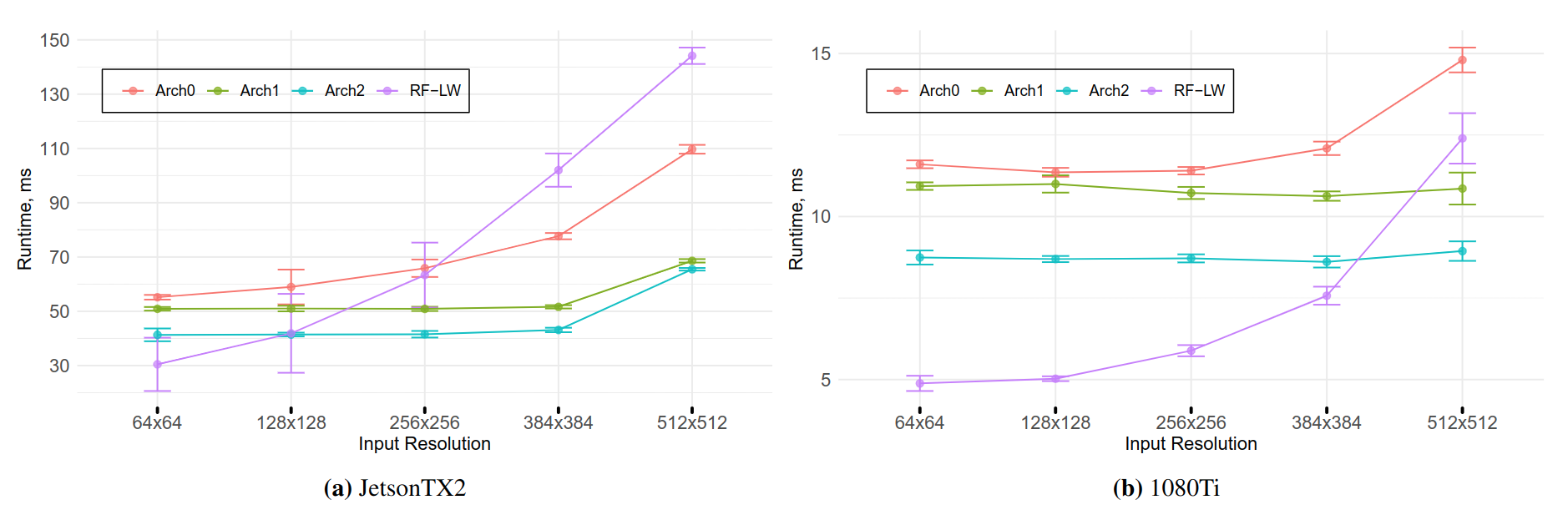

At Skydio I was working on the obstacle avoidance system and was fortunate to take part in building their second product. During that time I also realised the importance of certain choices made in industry that are often overlooked in the academic setting. First and foremost, I must mention the latency (running time) of modern neural networks. Even with architectural developments, most works focus on reducing their runtime using generic GPU cards and on small input-output resolutions. At the same time, embedded platforms (e.g. Jetson), have a limited memory throughput and scale poorly with higher-resolution inputs, which is especially evident when working with dense per-pixel tasks, such as semantic segmentation (see the plot below).

|

|---|

| Runtime of various segmentation networks as function of the input resolution (from Fast NAS of compact segmentation models via auxiliary cells, CVPR 2019 |

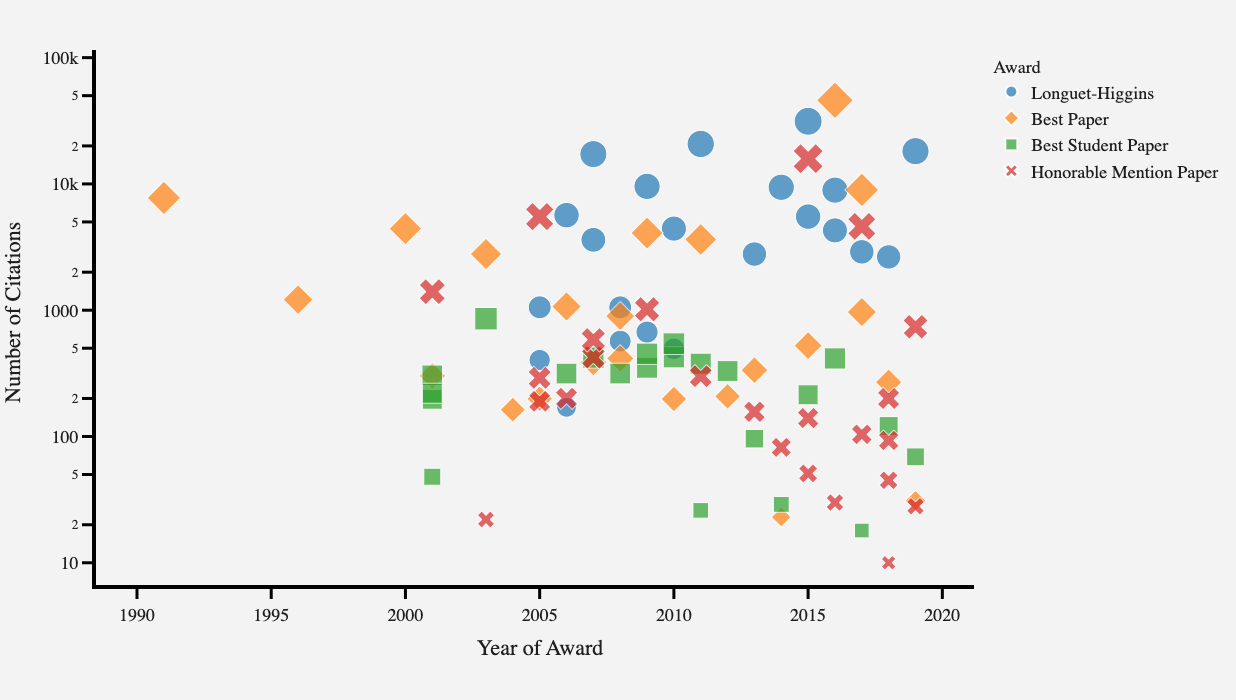

Secondly, the leaderboard metrics that we usually optimise for in academia, for example, mean intersection-over-union, are meaningless in isolation. In the real-world scenario, we must take into consideration not only per-class accuracies but also characteristics of the training / testing sets. Without those, you may end up with a completely wrong intuition about the way your algorithm performs. While seemingly obvious, many papers during the review phase of major computer vision conferences are solely judged on the state-of-the-art (SOTA) basis, which, in turn, serves as an encouragement for even more researchers to beat the SOTA without a second thought on how and why it is achieved. In short, I encourage not only to concentrate on quantitative improvements, but also on improvements in our understanding of what those quantitative metrics mean.

Finally, one of the crucial desiderata of autonomous systems is their stability. Currently we keep (re-)discovering how brittle neural networks can be. While it is quite unrealistic to come up with solutions that do not fail at all, it is important to build practical approaches that shed light on the sources of failures.

To conclude, I would encourage everyone deciding upon the choice of selecting either academia or industry is to try both sides before settling upon one or another. In my case, before the industry experience at Skydio, I was largely involved only in academia. While I enjoy doing research and spending time on building up my knowledge base, I also enjoy creating something that can be tested and used in the real-world situations, which was what this internship provided me with. Hence now knowing more about industry, I have a better understanding of what I would want to pursue when I end my PhD journey next year.

Comments