Neural Architecture Search at CVPR 2019

I decided to devote this post to neural architecture search (NAS) research that was presented at CVPR 2019 in Long Beach.

I believe that at some point every deep learning researcher and practitioner have spent a significant amount of their time thinking about what kind of architecture of a neural network to use for their particular problem. Mimicking AlexNet, then VGG, then ResNet, we all tried to come up with something effective. The famous “Grad Student Descent” definition also emerged around that time.

Now, I would have wanted to proudly announce that those times are gone!, but I will not; manually searching for an architecture is still kind of an exciting thing, isn’t it? Especially if you are supervising many students (just kidding).

Table of Contents

- Neural Architecture Search (NAS) – Primer

- NAS at CVPR 2019

- High-Level Summary

- Auto-DeepLab: Hierarchical Neural Architecture Search for Semantic Image Segmentation

- Searching for A Robust Neural Architecture in Four GPU Hours

- MnasNet: Platform-Aware Neural Architecture Search for Mobile

- RENAS: Reinforced Evolutionary Neural Architecture Search

- NAS-FPN: Learning Scalable Feature Pyramid Architecture for Object Detection

- IRLAS: Inverse Reinforcement Learning for Architecture Search

- Fast Neural Architecture Search of Compact Semantic Segmentation Models via Auxiliary Cells

- FBNet: Hardware-Aware Efficient ConvNet Design via Differentiable Neural Architecture Search

- Customizable Architecture Search for Semantic Segmentation

- Bonuses

- Conclusions

Neural Architecture Search (NAS) – Primer

So what is neural architecture search (or NAS) and why you should know about it (in case you completely missed out on last years of research)?

At the core of NAS is the idea of using a secondary algorithm (or search algorithm) to find for us the architecture structure for the problem that we care about. Going back to the infamous “Grad Student Descent”, if you are a professor who cares about problem A, you can can ask your students to come up with an optimal architecture for the problem – in this case, your secondary algorithm is your student(s), however cynical that might sound.

In the more ethical scenario, you would first define some sort of a search space of building blocks that would collectively define an architecture. Often, a configuration string describes the architecture – for example, given 3 layers (0,1,2, correspondingly) and 2 building blocks – conv1x1 and conv3x3 (A and B, respectively), the string “0A1A2B” will define an architecture x -> conv1x1 -> conv1x1 -> conv3x3. You can get creative with your search space however you want, but beware that the larger the search space the more iterations (hence, more GPUs) your secondary (search) algorithm would require.

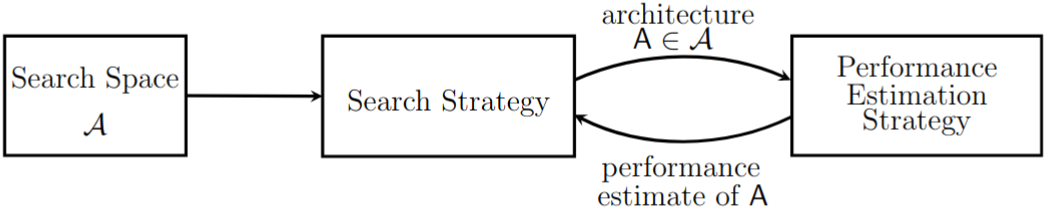

So what are the choices for the secondary algorithm? One of the earliest one is evolutionary search, where a population of architectures (i.e., multiple randomly initialised architectures) is being trained on the task of the interest (our primary problem) and being mutated (i.e., some parts of architectures are being mixed) based on their fitness score (also called reward – usually, validation metric for the given architecture). An alternative to that is reinforcement learning, where an agent (oftentimes, called controller) emits the configuration of the architecture; such an agent is usually represented as a recurrent neural network. The goal of the agent is to emit architectures that achieve higher rewards. Other choices for the secondary algorithm include gradient-based optimisation, where a large graph of all possible architectures is initialised with a learnable real-valued scalar assigned alongside each edge (building block) – intuitively, the scalar represents the probability of choosing the edge; and Bayesian optimisation, where the space is traversed based on some sort of a heuristic, for example, the heuristic might be a surrogate function that predicts the accuracy estimate of the sampled model.

|

|---|

| High-level representation of NAS. Figure from Elsken et. al |

For those interested to find out more about details of those algorithms I would refer to this wonderful survey by Elsken et. al. They also maintain a website where you can see recent related papers.

NAS at CVPR 2019

I will now turn my attention to works on NAS presented at CVPR 2019. If you want only high-level summaries, I provide the table below that includes links to the papers and code (if any), choices of search algorithm, domain and resources required. If I did not mention your paper, chances are I simply missed it – feel free to let me know about it. All the CVPR papers are available via this link.

High-Level Summary

| Name | Code | Optimisation | Search Domain | GPU-Hours |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auto-DeepLab | Yes | Differentiable | Segmentation | 72 |

| Robust Search | Yes | Differentiable | Image classification / Language Modelling | 4 |

| MnasNet | Yes | RL | Image classification | 6912 (TPU) |

| RENAS | - | RL + Evolutionary | Image classification | 144 |

| NAS-FPN | - | RL | Object detection | 120 (TPU) |

| IRLAS | - | RL / Differentiable | Image classification | - |

| FastDenseNAS | Yes | RL | Segmentation | 192 |

| FBNet | Yes | Differentiable | Image classification | 216 |

| CAS | - | Differentiable | Segmentation | - |

Auto-DeepLab: Hierarchical Neural Architecture Search for Semantic Image Segmentation

Anyone working in semantic segmentation is probably aware of the DeepLab team that keeps coming up with new ideas and keeps pushing the boundaries of the semantic segmentation performance with even better models. This time the authors resorted to the neural architecture solution to find architectures suitable for semantic segmentation.

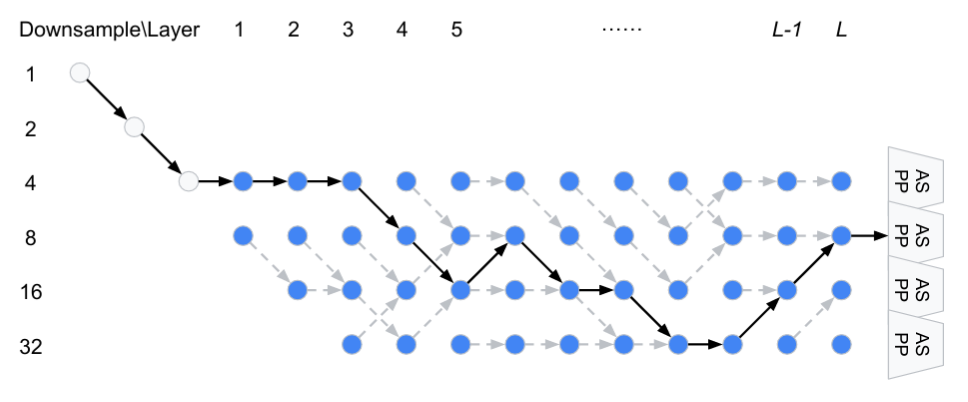

In the essence, this work is a straightforward adaptation of DARTS; for those not familiar, DARTS is a stochastic optimisation (gradient-based) method which initialises all possible architectures at once and optimises not only the weights of the parameters but also scalar weights (representing probability of choosing a certain edge) on each path. Here, the authors went one step further and, in order for the model to be suitable for semantic segmentation, they also optimised for the striding operations, namely, whether from a certain point in the graph to downsample the feature map, keep it intact, or upsample. As a result, they were able to find architectures that perform nearly on par with DeepLab-v3+ using one P100 GPU over 3 days.

|

|---|

| Example of structure discovered by AutoDeepLab. Figure from Liu et. al |

Interestingly, the authors do not pre-train found architectures on ImageNet, instead the training is done from scratch on CityScapes and ADE20K, while for PASCAL VOC they utilise MS COCO as commonly done. As written in the paper, “We think that PASCAL VOC 2012 dataset is too small to train models from scratch and pre-training on ImageNet is still beneficial in this case”. It would be interesting to see the effect of ImageNet on all the datasets that they used, to be honest; would such pre-training lead to better results on CityScapes?

Searching for A Robust Neural Architecture in Four GPU Hours

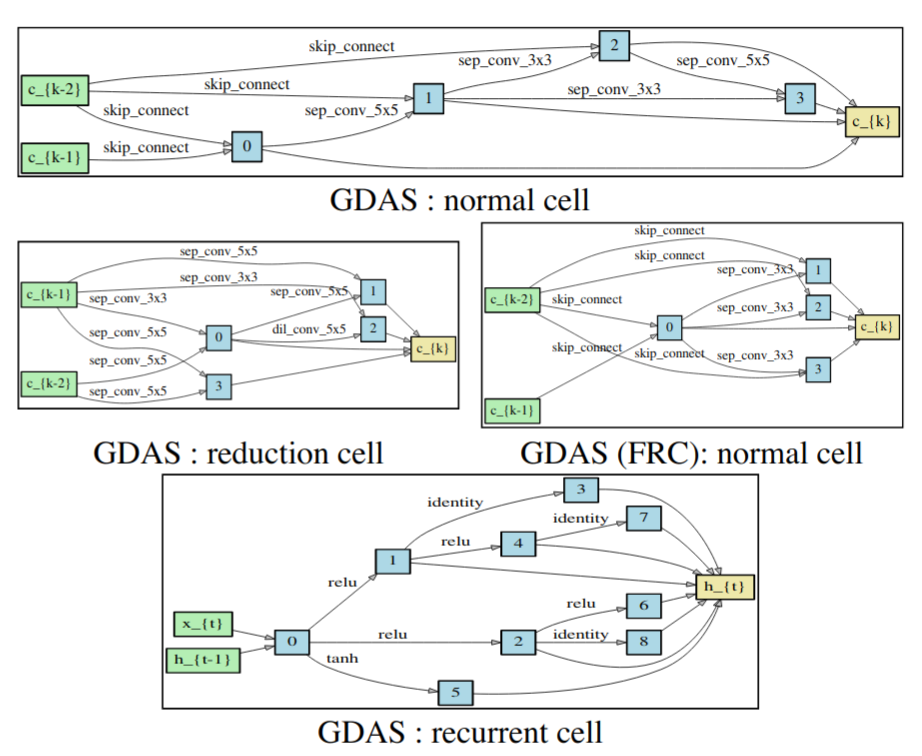

In this paper the authors combine best of both worlds from ENAS and DARTS. I already mentioned DARTS above; ENAS is an RL-based approach proposed by Pham et. al in which a large graph is also initialised in the beginning similar to DARTS, but instead of additional variables on edges, the RL-based controller decides which path is to be activated.

Here, the authors explicitly sample paths and optimise through them. Since the sampling is discrete, they rely on the Gumbel trick to back-propagate through. As the authors write “we use the argmax function … during the forward pass but the softmax function … during the backward pass …“. Overall, this approach leads to fast search on CIFAR-10 for image classification and Penn Tree Bank (PTB) for language modelling.

|

|---|

| Example of discovered cells. Figure from Dong and Yang |

Another trick that speeds up the training and reduces memory consumption is the direct consequence of using argmax in the forward pass – with it in-place, you only need to backpropagate the gradient generated at the selected index. The authors claim that with batch-training other layers are still getting some gradients due to each batch going through different paths.

MnasNet: Platform-Aware Neural Architecture Search for Mobile

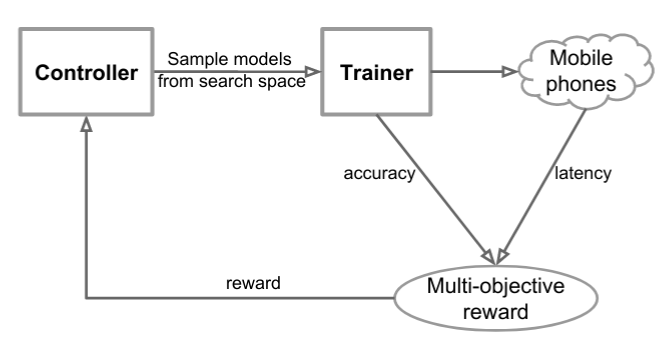

In this work, the authors consider one of important applications of NAS – search for architectures suitable for fast inference on mobile devices. In order to achieve that, they propose a multi-objective optimisation, where the RL-based controller is forced to output an architecture not only with a high score but also with low latency as measured on the CPU-core of Google Pixel 1. They consider the so-called Pareto optimality principle, which states that “the model is Pareto optimal if either it has the highest accuracy without increasing latency or it has the lowest latency without decreasing accuracy”. Based on it, they propose to use the weighted product of both metrics – i.e., accuracy and latency – as their reward signal.

|

|---|

| Overview of Mnas approach for architecture search. Figure from Tan et. al |

Additionally, in oder to allow highly effective but still feasible to search space, the authors define so-called “blocks” of layers; in each block the same layer is repeated for N times – the type of layer and the number of repeats are predicted by the RL-agent. Overall, the architecture design is motivated by MobileNet-v2, hence one can think of MnasNet as fine-tuning (and quite expensive one computationally) of its architecture using RL.

RENAS: Reinforced Evolutionary Neural Architecture Search

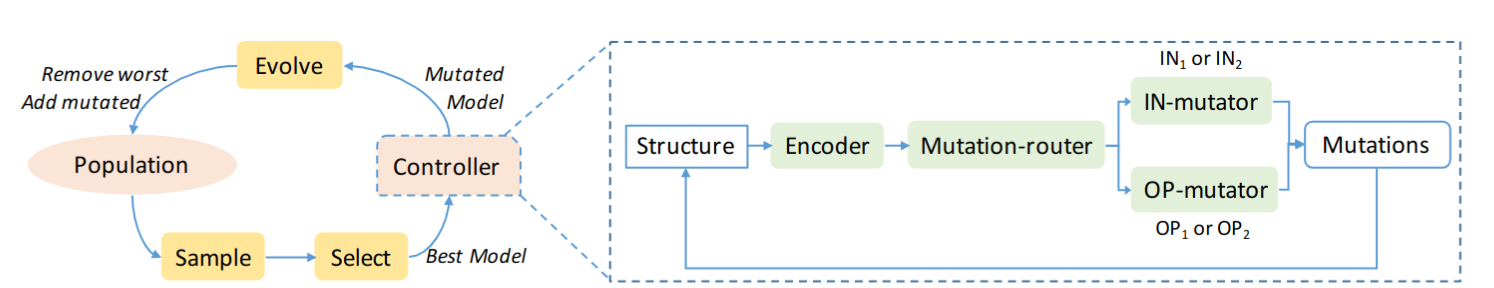

Here the main idea is to enhance the mutation mechanism of the tournament selection algorithm with a differentiable RL-based controller.

In more details, in tournament selection a population of architectures (aka individuals) is randomly initialised. After each individual is trained, its fitness is defined as the validation score. The fittest individual from the population is then mutated (i.e., some layers and operations are changed) to produce a child. In this work, the authors add the controller that defines how to mutate the given network. To speed up the training, the children models inherit parameters from their parents.

|

|---|

| Evolutionary search with reinforced mutation. Figure from Chen et. al |

NAS-FPN: Learning Scalable Feature Pyramid Architecture for Object Detection

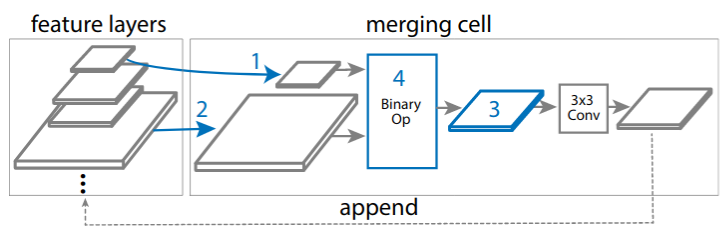

In yet another work on neural architecture search the authors consider the automatic way of improving object detection networks. Over the last years, feature pyramid network (FPN) has become an important part of all top-performing object detectors. In the essence, FPN acts as the progressive decoder of multi-scale features extracted from the network backbone (the encoder). Hence, the motivation of this paper is to search for better ways of combining multi-scale information starting from some initial backbone architecture.

To this end, the authors design the search space of merging cells that take as input multi-scale features and output their refined versions with the same resolutions. Inside the merging cell, two input layers (might be of different scale) together with the output scale and aggregation operation (either sum or attention-based global pooling) are being selected by an RL-based controller. The output of the merging cell is appended to the sampling pool so it can be selected on the next step.

|

|---|

| Merging cell structure. Figure from Ghiasi et. al |

The authors note that the design of the merging cell permits “anytime detection” since multiple cells can be stacked together and the forward propagation can be stopped after any of them. To speed up the search process, they rely on ResNet-10 with 512x512 inputs.

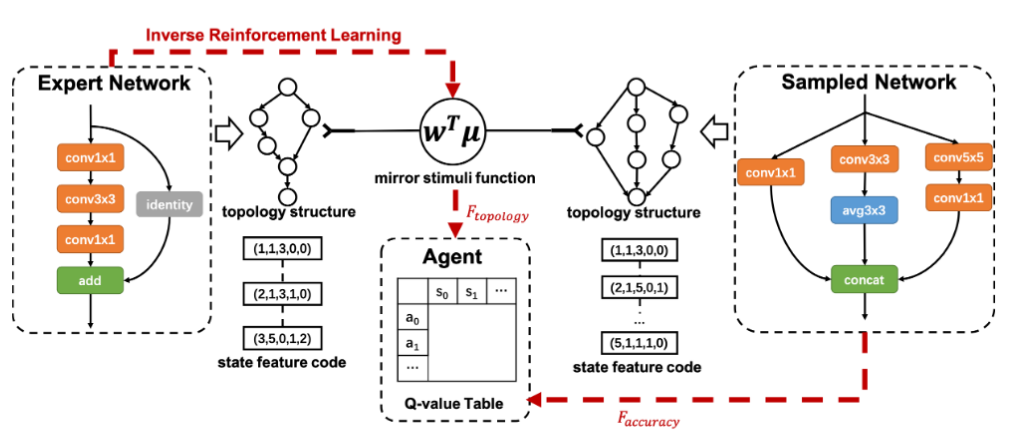

IRLAS: Inverse Reinforcement Learning for Architecture Search

Here the authors make the following observation: architectures manually designed by humans tend to have more elegant topology than their counterparts that were designed automatically. The topology, in turn, defines the network latency and memory requirements. Instead of setting up a specific resource-based objective, the authors force the sampled architecture to mimic the topology of some expert model (in this case ResNet). The imitation part is provided as an additional term in the reward objective.

|

|---|

| Overview of IRLAS. Figure from Guo et. al |

I personally like the idea of distilling the knowledge about existing architectures in order to train better NAS models, and it would be interesting to see whether the authors could come up with the solution that uses multiple expert networks instead of only one.

Fast Neural Architecture Search of Compact Semantic Segmentation Models via Auxiliary Cells

Spoiler: I am a co-author of this paper so my views might be biased.

Traditionally, RL-based algorithms for NAS require tons of GPU-hours (or TPU, if you are lucky to have them). While for image classification tasks the search can be performed with significantly smaller proxy datasets, such as CIFAR-10, in case of dense-per-pixel tasks, such as semantic image segmentation, it is unclear what proxy sets to utilise and how. Additionally, training of segmentation networks takes much more time and resources.

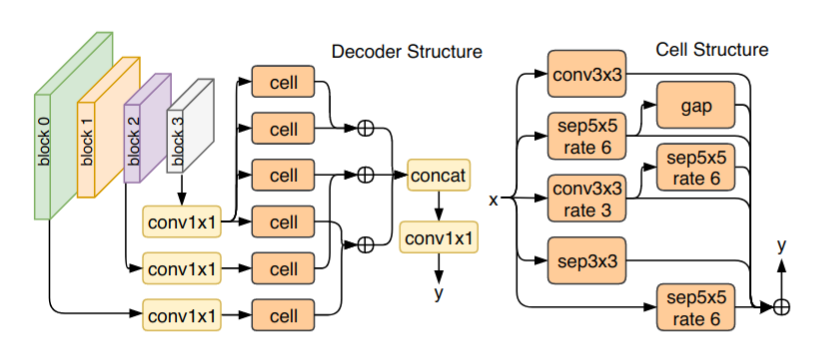

Hence, in this paper we concentrate on how to speed-up the inner loop of the RL-based NAS solution for semantic segmentation: namely, the training and evaluation of the sampled architecture. Starting from a pre-trained image classifier (here, MobileNet-v2), we only search for the decoder part. To this end, we propose several tricks to speed up the convergence of the sampled architecture: 1) we perform two-stage training with early stopping. During the first stage, we pre-compute the encoder’s outputs and only train the decoder. If the reward achieved after this stage is lower than the running average of rewards, we terminate the training; otherwise, we train the whole network end-to-end in the second stage. 2) We rely on knowledge distillation and Polyak averaging to speed up the convergence of the decoder part. 3) Finally, we also leverage intermediate supervision – but instead of simply using a single layer to perform segmentation, we over-parameterise the intermediate segmenters using the design structure emitted by the RL-based controller. We conjecture that for compact networks this over-parameterisation is helpful as a) it provides smoother gradients to the main branch, and b) it frees up the task demand on the shallow intermediate layer.

|

|---|

| Example of discovered architecture for semantic segmentation. Figure from Nekrasov et. al |

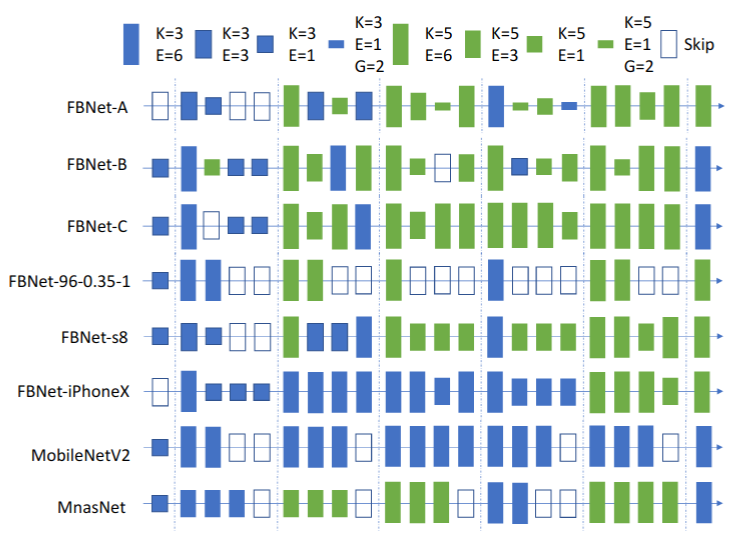

FBNet: Hardware-Aware Efficient ConvNet Design via Differentiable Neural Architecture Search

As in some of the above works, here the authors initialise the search space as a large graph of different layers and rely on the differentiable stochastic optimisation with the use of the Gumbel trick. In addition, they use a lookup table model for measuring latency of each building block of the generated path. Differently from other works that search either for one or two building blocks (aka cells), here the authors define the general outline of the architecture (macro-space), define candidate blocks at each layer and search for each one of them independently (micro-space).

|

|---|

| FBNet discovered architectures. K stands for kernel size, E – for expansion rate, and G – for group-factor in convolution. Figure from Wu et. al |

Interestingly, the authors target mobile devices such as Samsung Galaxy S8 and use the int8 data type for inference. Furthermore, they showcase that by targetting different devices it is possible to discover better device-specific networks (as the latency lookup table is device-specific).

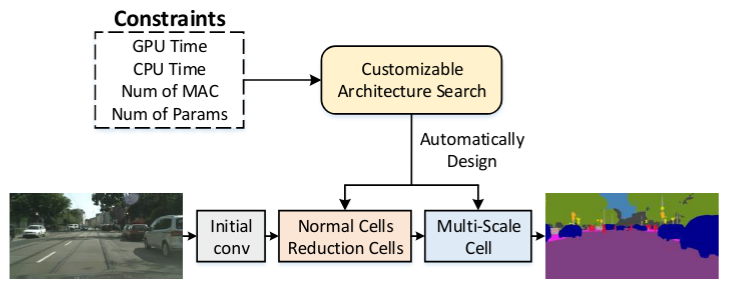

Customizable Architecture Search for Semantic Segmentation

The authors adapt the DARTS algorithm for semantic segmentation and design their search space with three types of cells: normal and reduction cells as in image classification, and multi-scale cell inspired by ASPP. An additional objective, a cost of selecting a particular operation, is optimised together with the task-specific loss. To assign the cost to the given operation, the authors propose to measure the difference in either latency, number of parameters or FLOPs, between all the cells built using only the given operation and the cells with only the identity operation.

|

|---|

| Resource-based search for semantic segmentation. Figure from Zhang et. al |

The authors first search for the segmentation backbone consisting of the normal and reduction cells, then fine-tune it on ImageNet before searching for the multi-scale cell. Surprisingly, such a crude approximation to the cost of each operation still leads to the discovery of compact and accurate networks.

Bonuses

Two papers that are not directly related to NAS, but might still be of interest to some folks.

MFAS: Multimodal Fusion Architecture Search

In this paper the authors consider the problem of multi-modal fusion – i.e., given multiple modality-specific networks find the optimal way of connecting their hidden layers in order to maximise performance on the task of interest. For example, one popular strategy is late-fusion, where the last features from each network are aggregated (e.g., via summation). Here, the authors posit this problem as that of neural architecture search, where instead of finding the network from scratch, the search is only for connections between already pre-trained networks.

To this end, the authors leverage sequential model-based optimisation (SMBO), where a separate function, oftentimes called “surrogate” is used to predict the accuracy of the sampled architectures. Importantly, the search starts from a small set of architectures in order to pre-train “surrogate” with the size of architectures constantly growing. One example of this within the traditional NAS framework is Progressive NAS.

As a result of that, the authors discover several fusion structures on the MM-IMDB dataset for predicting movie genres from posters and movie descriptions, and on NTU RGB-D for activity recognition from pose and RGB data.

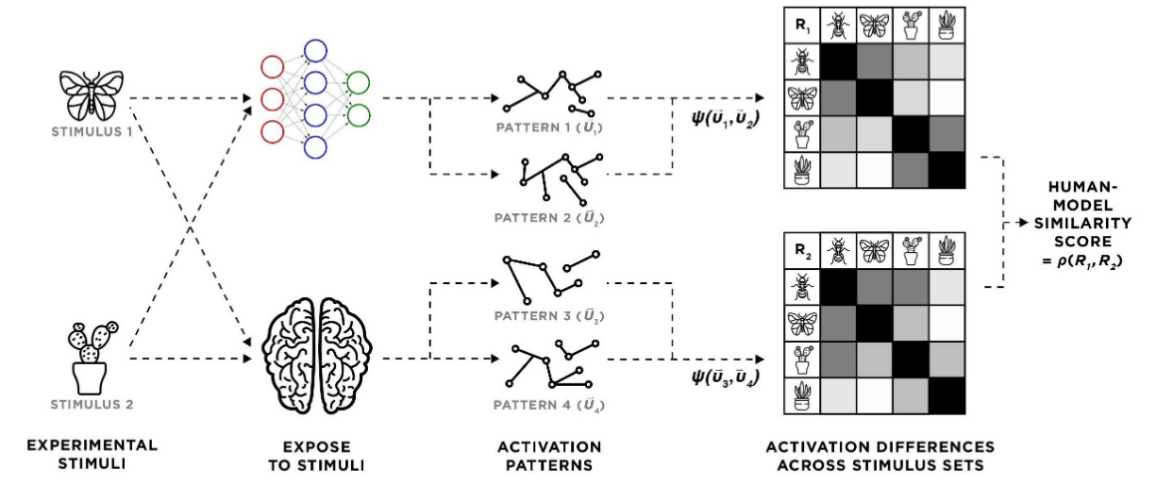

A Neurobiological Evaluation Metric for Neural Network Model Search

In neuroscience, there is a theory stating that similar objects cause similar neural responses in human brains. Based on that, the authors conjecture that neural networks with activations similar to brains, must also demonstrate stronger generalisation capabilities. To this end, they propose to use a human-model similarity (HMS) metric that allows them to compare human fMRI with the network activation behaviour. At this point, I must say that the network they are considering is so-called PredNet suitable for unsupervised video prediction – i.e., given the current frame it predicts what is going to happen next.

To define HMS, the authors build up representational dissimilarity matrices (RDMs) that quantify responses of two systems (here, network and brain) to pairs of stimuli. Given two RDMs, HMS is defined as a Spearman’s rank correlation between them.

|

|---|

| Computational flow of the HMS metric. Figure from Blanchard et. al |

Notably, the authors find that HMS positively correlates with the validation accuracy, suggesting that HMS might be used as a guiding metric for finding generalisable networks and to perform early stopping. Importantly, to compute HMS the method only requires 92 stimuli. It would be interesting to see how this direction of research that ties up biological principles with artificial neural networks will evolve in next years.

The code is available here.

Conclusions

Although I would not necessarily call CVPR 2019 as a breakthrough venue for NAS, it is exciting and liberating to see a large proportion of papers overcoming the needs of “however many GPUs / TPUs” you have, and achieving comparable results. It would be definitely interesting to see how NAS will progress and what other tricks researchers will come up with.

One point I would mention is that searching for non-image-classification architectures from scratch is still challenging; this year we saw several adaptation of RL-based (NAS-FPN, FastDenseNAS) and differentiable optimisation-based (AutoDeepLab, CAS) for semantic segmentation and object detection. All of those have to make some sacrifices and either search for only a limited number of layers (the RL-based ones), or pre-define the large structure in the beginning of the search (the DARTS-like one). As we witnessed the progress of semantic segmentation around 2015, most works at first were a direct adaptation of image classifiers (see seminal work by Long et al), but gradually segmentation-specific research have grown in scope with task-specific contextual structures emerging (e.g., ASPP, PSP, RefineNet, etc.). Soon I believe we will also be witnessing more works tailored for architecture search of specific tasks, other than image classification and language modelling.

I am thankful to Hao Chen for reading through the first draft of this article and giving helpful suggestions and comments

Comments